St James, open - although I got locked into the car park and had to exit cross country - is a foursquare church more in the Essex vernacular than Herts, which is slightly odd to find this far west. The octagonal stair turret adds to the external charm and whilst the usual Herts refurb is obvious it's not quite as in your face as others. Inside there's a good pulpit, remnants of old, and some nice newer, glass and a set of Queen Anne's arms. Not a great church but nevertheless pleasing.

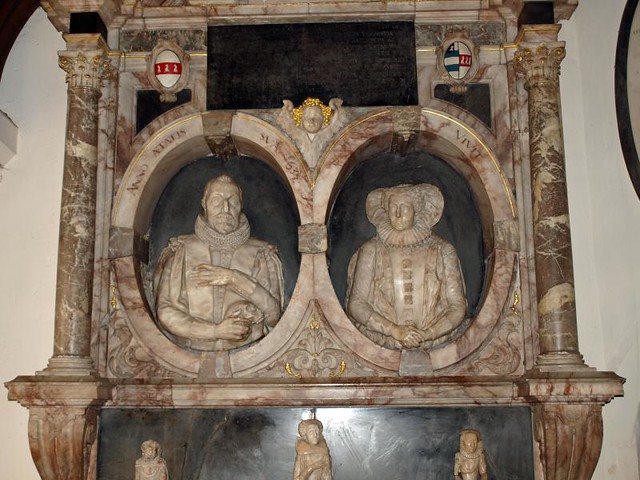

ST JAMES. In a neatly kept churchyard at an equally well kept widening of the High Street. Flint, with a C13 chancel, a higher C15 nave and W tower with big diagonal buttresses and a NE stair-turret, and C19 aisles and N porch. On the inner N and S walls of the chancel tall wide blank arcading with Purbeck marble shafts and moulded capitals. The N and S lancet windows are also original. The chancel is separated from the nave by that rare feature a ‘tympanum’, that is a plastered partition with the Royal Arms (of Queen Anne), resting on a big beam. The nave roof is of the C15. - PULPIT. Jacobean with strapwork motifs; the tester is preserved. - CHANDELIER. Brass, C17 or C18, in the chancel. - PLATE. Cup and Paten, 1633; Flagon, 1634; Salver, 1671; Almsdish, Wafer Box and Wine Strainer presented in 1754; Set presented in 1887.

Bushey. Each year its houses spread a little farther, but the panorama from Bushey Heath remains a fair reward for climbing the hill from Watford, and an old inn hangs out its sign of The Merry Month of May as a reminder that that is the best time to come, when even the birds in the aviary of old Hartsbourne Manor park are chattering about spring.

The view has had its artists, for old Thomas Hearne, the painter who had something to teach Turner, lived and died here at the beginning of last century, and at the end of the century came Hubert Herkomer, followed by the younger artists flocking to his famous school. Two artists and a storyteller poet this village has known, and they lie in the churchyard of Bushey’s oldest church, St James’s, shaded by the park trees where the hill dips down to a deep valley. Perhaps no village in Hertfordshire has a more interesting group of graves in its churchyard than those of Thomas Hearne, Hubert Herkomer, and Barry Pain.

Thomas Hearne, an 18th-century water colourist who lived on till after Waterloo, did much to revive interest in Gothic architecture, and it is known that his work was an inspiration to the immortal Turner. There are fine collections of his drawings in the British Museum and at South Kensington. The first great experience he gave himself may seem to us extraordinary, for he went out to the Leeward Islands and spent three years sketching the life of the islands and their people. Then he came home and became one of our forerunners, for he made a grand tour of England, spending four years on it and making a great collection of drawings of our antiquities.

Sir Hubert Herkomer was the son of a Bavarian craftsman, who went out to America and then came to England, sending his son Hubert to the School of Art at Southampton. A picture of a Gipsy Encampment started him on his way, and in 1870, when he was 21, he was doing successful water colours. He took a cottage at Bushey, married, and in 1875 was a great success at the Academy with his famous painting of the Chelsea war veterans in their scarlet coats, The Last Muster. He settled down at Bushey in a house like a mountain schloss to which he brought his father and his grandfather, who enriched the house with their woodcarving. A delightful man, he longed to be not only a painter but a craftsman, and he wrote music and operas, designed scenes for the stage, took an interest in the early films, lectured everywhere, and died while holidaying in Devon, just before the war which would have broken his heart. In the years of depression that followed the Great War his palace of art has been pulled down because nobody wanted it.

Barry Pain was one of the bright writers of the last generation, humorist, poet, and storyteller. He wrote one of the most famous poems of the Great War, addressed to the Kaiser, who had telegraphed that God had magnificently supported them. These were the closing lines of Barry Pain’s poem:

Impious braggart, you forget;

God is not your conscript yet;

You shall learn in dumb amaze

That His ways are not your ways,

That the mire through which you trod

Is not the high white road of God.

To Whom, whichever way the combat rolls,

We, fighting to the end, commend our souls.

On his grave in Bushey churchyard, in which Barry Pain was laid in 1928, are the last words of another of his poems. He was dreaming that up in the sky he saw the army of the dead go by, and he called upon us all to pay homage in these words which are on his stone:

Look upward, standing mute; Salute.

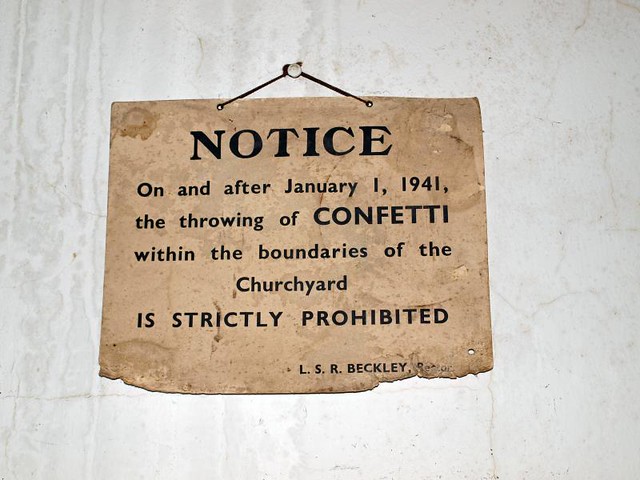

On another tomb in Bushey churchyard 12 loaves of bread used to wait for 12 poor people every Sunday morning, the gift of Dame Fuller of Queen Anne’s day who also endowed the Free School at Watford. A stone in the vestry, and his daughter’s stone outside, remind us that here, too, was laid to rest that humorous, vigorous Presbyterian Silius Titus, the Parliamentary colonel who turned Royalist and plotted to release Charles I while guarding him at Carisbrooke, though Cromwell grew suspicious and moved him from his post. Even then he continued to correspond with the king, and we can still read the letters the imprisoned king wrote to him. In the end he saw the return of the Stuarts and survived till the reign of the last of them.

Though most of the church to which all these folk made their last journey was made new at the end of last century, the fine open roof of the nave and the tower remain from the 15th century; there is an original bell. In place of a chancel arch is a 500-year-old beam supporting the arms of Queen Anne painted on plaster, and the side windows of the chancel are framed in shallow 13th-century wall arcades. The Jacobean pulpit, with its sounding board, is a mass of rich carving which must have delighted the old woodcarvers from Bavaria.

A little way off lies Bushey Heath, long noted among botanists for its wild lily-of-the-valley. From the stately tower of its modern church the valleys of the Thames and the Colne lie spread before us, and on a clear day we may see the red walls of Hampton Court and the round tower of Windsor Castle. It is from here, at Merry Hill, that Watford draws some of its water supply, a great reservoir 500 feet above the sea, holding two million gallons.

The impressive church has an attractive interior with windows from the workshops of William Morris, paid for largely by children who collected farthings. The Morris windows are in the baptistry and represent the Children of the Bible surrounding the Child of Bethlehem.