Their website does, however, offer contact numbers for non service visits (which is a bit useless if you haven't done previous research) and the Knebworth House Access Statement says that you can make an appointment to visit via the Estate Office prior to visiting.

I've marked it up as a revisit but I'm not sure I can be bothered to jump through the hoops required to gain access - if it was open alongside the house, which seems to me to be a perfectly reasonable expectation, it would be a no brainer.

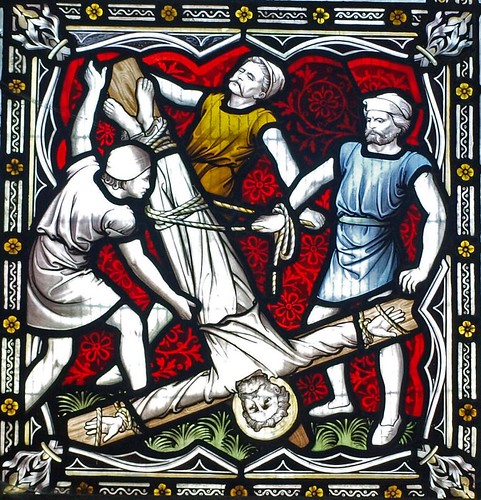

ST MARY AND ST THOMAS. The church stands in the grounds of Knebworth House, everywhere surrounded by fields but within a stone’s throw of the front terrace of the mansion. The exterior attractive owing to its position but architecturally insignificant: nave, chancel, C15 tower (diagonal buttresses, SE stair-turret higher than the tower, and spike), N chancel chapel (Lytton Chapel) added c. 1705 to house the new sumptuous family monuments. The interior has a low Norman chancel arch with one order of scalloped colonnettes and a blocked Norman chancel N window. - ALTAR TABLE. C18 on classical columns. - PULPIT. C18 with carved panels of Flemish origin; one of them dated 1567. - BENCHES. C15, of plain solid profile. - IRON GATES to the Lytton Chapel designed by Lutyens, also one of c. 1705 under the tower arch. This was originally in the arch between chancel and Lytton Chapel and is of excellent quality. - STAINED GLASS. Three-light window in S wall by Clayton & Bell, c. 1875. - PLATE. Chalice, C17; Paten, 1668. - MONUMENTS. The Lytton Chapel contains the most remarkable display of family pride in the county. The chapel is really far too small to hold the three marble tombs put up in it between 1705 and 1710. On the N and S walls Sir William Lytton d. 1705 and Sir George Strode d. 1707. These two are both by Edward Stanton whose signature on the former is almost too prominent. Both men are represented semi-reclining; they are stout and wear wigs, and their clothes are meticulously portrayed. They tell of much self-confidence and worldly success. Both monuments have reredos backgrounds, the former with detached columns, the latter with pilasters. The former, moreover, has life-size allegories standing outside the columns, which carry a coffered segmental arch. On the W wall is the monument to Lytton Lytton d. 1710, obviously by a different hand and the sign of a change in taste (Mrs Esdaile suggests Thomas Green): more classical and a little less Baroque (e.g. fluted pilasters instead of columns). Mr Lytton stands in the centre, a more than life-size portly figure, against an arched niche. - In the same chapel are Brasses to Roland Lytton d. 1582 and his two wives, a tablet to Anne Lytton d. 1601, with pretty thin ribbon-work on pilasters and frieze, and the epitaph to William Robinson Lytton Strode d. 1732 and his wife, two stiff kneeling figures facing a sarcophagus with a relief of allegorical putti, and another relief above. - This monument is signed by John Annis. - But the highest aesthetic quality and certainly the most discriminating taste is not to be found in the chapel but in the chancel: the epitaph to Judith Strode d. 1662: a surprisingly Roman looking frontal bust without any frills and furbeloes of dress, set against a background of black marble as noble in shape and sophisticated in detail as any by the Florentine Mannerists of the C16. - Also in the chancel Brass to Simon Bache d. 1414, priest, frontal with figures of saints in the orphreys of his cope.

Knebworth. Modern Knebworth on the Great North Road has a church on the hillside, reached by an avenue of limes, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, with great eaves overhanging the brick walls, and an unusual interior with many pillars and arches, two huge pillars at the crossing reaching to the roof.

Written in Domesday Book as Cheneepeworde, old Knebworth, a mile to the west, has an old church in the 260-acre park, looking from its lawn to the great house with its medley of towers and domed turrets, famous for its beautiful grounds and as the home of Bulwer-Lytton and his ancestors. There have been Lyttons at Knebworth for over four centuries. Many of them sleep in the church, but the most famous of them earned his resting-place in Westminster Abbey.

Beginning as a simple nave and chancel in the 12th century, the church received its tower in 1420, the Lytton chapel 100 years later, and the porch perhaps in the 17th century; but the chapel was rebuilt about 1700 and the chancel in the 19th century. The roofs are of mellowed tiles. The nave has leaning walls, medieval windows, 15th-Century oak benches, and a roof with its old traceried trusses over the hammerbeams. In the old oak pulpit are still older Flemish panels carved with scenes in the Life of Our Lord, one on the stairway dated 1567. The font is about 1480, and one of the old rood stair doorways is blocked. The fine iron screen across the tower arch is 18th century. Still entered by a simple Norman arch, the chancel has the arch of a Norman window in the north wall, a 15th-century piscina, and a 17th-century Italian painting of the Last Supper over the altar. The Madonna and St Thomas of Canterbury, patron saints of the church, are in the west window of the tower.

Crowded with memorials, the small chapel has all the pomp that 18th-century marble monuments can give. Of three which are railed round and nearly reach the roof, one has a lavish canopy on Corinthian columns, under which Sir William Lytton of 1704 lies in his lace cravat and cuffs. In the second monument Lytton Lytton of 1710 stands on a pedestal, under a classical pediment, wearing a long, curling wig and a long, buttoned coat with a cravat; at the sides cherubs are weeping. He died at 21, having changed his surname of Strode on inheriting the estate, which at his death went to the Robinsons, his mother’s family. The third great monument shows his father, Sir George Strode of 1707, in similar dress; he sleeps at Etchingham, Sussex. Sir George’s mother was Judith Lytton, who has a memorial with her bust in the chancel; she died aged 23 in 1662, and by her floorstone is a small stone to one of her three children, with the words: Judith, the one-year-old little daughter qf Nicholas and Judith, lies next to her mother.

The three names were borne by William Robinson Lytton Strode of 1732, who kneels with his wife in a dainty monument with a sarcophagus and three children playing with an hourglass, a skull, and a serpent with its tail in its mouth - symbols of mortality and eternity. A fine brass in the chapel has portraits of Sir Rowland Lytton of 1582, his two wives in gowns with ruffs and brocaded petticoats; we read that he was a gallant leader in war and a worthy magistrate in peace. He was knighted by Elizabeth I, and entertained her at Knebworth. In the chancel is a beautiful brass portrait of a priest, Simon Bache of 1414, with rather sour expression; the engraving is deep and rich; his cope is adorned with saints, wonderful in detail, and on the clasp is the head of Our Lord.

All that is left of the tomb and brass portraits of Sir John Hotoft and his wife are three shields and a few strips of the brass inscription. Sir John, who was given the estate by Henry IV and was Treasurer of the Household of Henry VI, is said to have restored the nave and built the tower; his arms are on the west doorway. One of his daughters married Sir Richard Lytton; the other inherited Knebworth.

An inscription tells of Captain Charles Earle, who fought in the Kaffir War and at the Relief of Lucknow, and served the Lyttons for 20 years. We read of Fraser Campbell Buchanan, killed at Arras when he was 23, and see beautiful Whall glass in a window to Leslie Amott Paterson, who also fell; it shows a knight setting forth to the fight, and unbuckling his armour when it was over.

At the entrance to the chapel is a beautiful iron screen surmounted by a golden cross which bears a winged sword and has 29 stars in its 57 rays of light. Screen and cross are in memory of Viscount Knebworth, who was 29 when he was killed while flying at Hendon in 1933, when his father was 57. Designed by his uncle Sir Edwin Lutyens, the screen was made in Hatfield and the cross in London. On a silver cross on the altar in the chancel are the words, In memory qf Anthony, May 1st, 1933; an offering from his mother.

Sir Edwin designed the beautiful memorial marking the airman’s grave in a garden of remembrance to the east of the churchyard, shaded with silver birch trees. On a flat stone is carved the winged sword emblem of the Auxiliary Air Force, in which he was a pilot. The headstone is a frame for a lovely figure of a woman with her hair in long plaits and a crown of stars on her head. Holding a sphere on which is a falcon, she represents Our Lady of the Sky, sculptured by Sir William Reid Dick. Seven shields on the back of the stone include those of his parents, Eton, Magdalen College, the City of Westminster, and Hertfordshire. A stone with five cherub heads round a star, marking the grave of Annie Louisa Sleath who was “forty years friend and Nannie of the Lutyens family, was designed by Sir Edwin.

The great Tudor house Sir Robert Lytton began to build was completed during the 16th century. Its original plan was of four sides enclosing a courtyard, and so it stood till the 19th century, when three generations of the family made it the house we see. The great transformation began in 1811 with the pulling down of three wings; then came the lavish enrichment of the remaining west wing with battlements, panelled turrets crowned with copper domes, stringcourses dotted with flowers and grotesques, dragons on pinnacles, and faces and gargoyles peeping out everywhere. The south wing with its tower-gateway was added last century. The wall round the other sides of the court is adorned with quatrefoils, and dragons holding shields are on the gateposts. The grounds are delightful with spacious lawns, formal avenues of pollarded limes, and carpets of primroses, daffodils, and narcissi under trees. A great almond tree is an entrancing sight in spring. There are noble avenues in the park, and near the church is a stone mausoleum decorated with urns and crowned with a sarcophagus.

The three rooms in the house which all may see belong mostly to the old mansion. As we enter we come upon a fine bronze bust of the earl of our time, Viceroy of India. In the staircase hall is a saddle and halter embroidered in solid silver, the gift of the Emir of Afghanistan to the first earl when he, too, was Viceroy. Here is a big array of armour of Queen Elizabeth I’s day, and some from the time of Cromwell; the Dutch musical clock is about 1700. Bulwer-Lytton converted the next room into the library, and here we see the novelist’s writing-table with his ink-stand, cigar-case, and blotting-pad. First editions of his works are on the shelves, and in a case are manuscripts of The Last Days of Pompeii, The Caxtons, and My Novel, a cast of the author’s hand, and letters he received from Charles Dickens. In the same case is the manuscript of Lucile, a novel in verse written by his son, the first earl, under the name of Owen Meredith. Treasured in another case are snuff-boxes which belonged to Charles Fox and William Pitt, Lord Byron’s ruler, a crucifix of gold and pearls which belonged to Mary Queen of Scots, the ink-stand used for the signing of the treaty between Charles I and the Commissioners of the Long Parliament, and a ring with a miniature of the king. It was one of three which Charles gave to his friends on the scaffold. Furnishing the library are chairs of the time of William and Mary and Queen Anne, and a 17th-century Spanish cabinet made of tortoiseshell, ebony, ivory, and gilt metal; and there is a long wooden pipe shown in a portrait of the novelist over the mantelpiece.

By a door disguised among the shelves of books we come to the charming white drawing-room, where nothing was lovelier when we called than the window peep of the laburnum trees flowering in a corner like a shower of gold. Here we see Sir Robert, the first Lytton of Knebworth, and among other family portraits are Peter Lely’s Ruth Barrington and Sir William Robinson Norreys. Hepplewhite and Chippendale are represented among the furniture; there are two tortoiseshell and ivory English cabinets of the time of Charles II, and another Spanish one of the same century. By Daniel Maclise’s portrait of Bulwer-Lytton as a young man is a door leading to the banqueting hall, a splendid chamber with an oak ceiling, screen, and gallery from the time of James I, and rich panelling said to have been designed by Inigo Jones. Most of the furniture here is Jacobean, but includes a valuable set of 12 applewood chairs, made in the time of Charles II. Portraits include one of the Duke of Gloucester, son of Charles and Henrietta Maria. Hanging here is a banner with the Lytton arms which hung above the throne from which Lord Lytton proclaimed Queen Victoria Empress of India at the great Durbar of 1877. One of the bedrooms has a noble four-poster richly carved in oak, in which Elizabeth I is said to have slept.

The first Lord Lytton was one of the most versatile men of all time in England. He was a novelist, dramatist, and politician, and succeeded in every ambition, though not to the extent of high and lasting eminence.

He was born in London in 1803, and brought up by his mother, his father dying when the son was four years old. From childhood he wrote poetry, and was expected to become a notable man. At Cambridge he took the Chancellor’s medal for a poem on Sculpture. He found popularity in prose when he was 25 with his novel Pelham, and he needed it, for he had only inherited £200 a year from his father, and his mother, who was well-to-do, had cut him off for marrying against her wishes. That marriage was a complete failure, except that from it have followed two generations of Lyttons honourably distinguished by public service. Lytton and his clever but hysterical wife could not live together, and they separated.

He soon had an ample income from his writings. Eventually the standard edition of his novels was issued in 48 volumes. The most striking feature of this enormous production, which was spread over nearly 50 years, was its variety in character and in style. His first series of stories, beginning when Scott was nearing the end of his wonderful career and before Dickens began his, owed something to the craze of Byronism, but soon became deflected into a study of crime, not unlike the crook element in fiction a century later. It began incidentally in Pelham, and continued in Disowned, Paul Clifford, and Eugene Aram, with Paul Clifford the highwayrnan as its most typical and popular example. Then he turned to history, with an attempt to build up round a central character a picture of a succession of ages past. The Last Days qf Pompeii, Rienzi, The Last of the Barons, and Harold illustrate this phase of his progress, for progress it was. He tried drama, not unsuccessfully in The Lady qf Lyons, Richelieu, and Money, plays that have attracted the public, in later years. In poetry he essayed the satirical and the romantic, but he failed in both. He made a vicious attack on Tennyson, who was then emerging into fame, and Tennyson retorted, in a poem that is not reproduced in his collected works, and (as Andrew Lang has said) knocked Lytton out in the first round.

Lytton now turned to the staple theme of fiction, the ordinary life of the people, and wrote his best novel The Caxtons, which was followed in the same quiet spirit but not with equal success by My Navel and What Will He Do With It? Later he sought to picture society and art as he saw them towards the end of his life in France and England, in contrast with what he had known in more aristocratic days. From time to time all through his life there was a strain of the eerie and abnormal in him, and in one of his last books, The Coming Race, he experimented in imaginative prophecy. He saw mankind’s powers of catastrophic destruction ensuring peace. Such an extraordinary range of interest in so many books could hardly be sustained, and Lytton, especially in his early periods, was often extravagant and melodramatic. He was adept in following popular fashions, and so failed in creating a style of his own. Though unquestionably clever, he never crossed the boundary line of greatness.

He sat in Parliament as a Whig for ten years and was offered a lordship of the Admiralty, but declined it. In 1852 he returned to Parliament as a Conservative, and was decidedly successful as a speaker. He served as Secretary for the Colonies, and was made a peer as Baron Lytton. Thrice he was elected Rector of Glasgow University. He died at Torquay in his 70th year.

Written in Domesday Book as Cheneepeworde, old Knebworth, a mile to the west, has an old church in the 260-acre park, looking from its lawn to the great house with its medley of towers and domed turrets, famous for its beautiful grounds and as the home of Bulwer-Lytton and his ancestors. There have been Lyttons at Knebworth for over four centuries. Many of them sleep in the church, but the most famous of them earned his resting-place in Westminster Abbey.

Beginning as a simple nave and chancel in the 12th century, the church received its tower in 1420, the Lytton chapel 100 years later, and the porch perhaps in the 17th century; but the chapel was rebuilt about 1700 and the chancel in the 19th century. The roofs are of mellowed tiles. The nave has leaning walls, medieval windows, 15th-Century oak benches, and a roof with its old traceried trusses over the hammerbeams. In the old oak pulpit are still older Flemish panels carved with scenes in the Life of Our Lord, one on the stairway dated 1567. The font is about 1480, and one of the old rood stair doorways is blocked. The fine iron screen across the tower arch is 18th century. Still entered by a simple Norman arch, the chancel has the arch of a Norman window in the north wall, a 15th-century piscina, and a 17th-century Italian painting of the Last Supper over the altar. The Madonna and St Thomas of Canterbury, patron saints of the church, are in the west window of the tower.

Crowded with memorials, the small chapel has all the pomp that 18th-century marble monuments can give. Of three which are railed round and nearly reach the roof, one has a lavish canopy on Corinthian columns, under which Sir William Lytton of 1704 lies in his lace cravat and cuffs. In the second monument Lytton Lytton of 1710 stands on a pedestal, under a classical pediment, wearing a long, curling wig and a long, buttoned coat with a cravat; at the sides cherubs are weeping. He died at 21, having changed his surname of Strode on inheriting the estate, which at his death went to the Robinsons, his mother’s family. The third great monument shows his father, Sir George Strode of 1707, in similar dress; he sleeps at Etchingham, Sussex. Sir George’s mother was Judith Lytton, who has a memorial with her bust in the chancel; she died aged 23 in 1662, and by her floorstone is a small stone to one of her three children, with the words: Judith, the one-year-old little daughter qf Nicholas and Judith, lies next to her mother.

The three names were borne by William Robinson Lytton Strode of 1732, who kneels with his wife in a dainty monument with a sarcophagus and three children playing with an hourglass, a skull, and a serpent with its tail in its mouth - symbols of mortality and eternity. A fine brass in the chapel has portraits of Sir Rowland Lytton of 1582, his two wives in gowns with ruffs and brocaded petticoats; we read that he was a gallant leader in war and a worthy magistrate in peace. He was knighted by Elizabeth I, and entertained her at Knebworth. In the chancel is a beautiful brass portrait of a priest, Simon Bache of 1414, with rather sour expression; the engraving is deep and rich; his cope is adorned with saints, wonderful in detail, and on the clasp is the head of Our Lord.

All that is left of the tomb and brass portraits of Sir John Hotoft and his wife are three shields and a few strips of the brass inscription. Sir John, who was given the estate by Henry IV and was Treasurer of the Household of Henry VI, is said to have restored the nave and built the tower; his arms are on the west doorway. One of his daughters married Sir Richard Lytton; the other inherited Knebworth.

An inscription tells of Captain Charles Earle, who fought in the Kaffir War and at the Relief of Lucknow, and served the Lyttons for 20 years. We read of Fraser Campbell Buchanan, killed at Arras when he was 23, and see beautiful Whall glass in a window to Leslie Amott Paterson, who also fell; it shows a knight setting forth to the fight, and unbuckling his armour when it was over.

At the entrance to the chapel is a beautiful iron screen surmounted by a golden cross which bears a winged sword and has 29 stars in its 57 rays of light. Screen and cross are in memory of Viscount Knebworth, who was 29 when he was killed while flying at Hendon in 1933, when his father was 57. Designed by his uncle Sir Edwin Lutyens, the screen was made in Hatfield and the cross in London. On a silver cross on the altar in the chancel are the words, In memory qf Anthony, May 1st, 1933; an offering from his mother.

Sir Edwin designed the beautiful memorial marking the airman’s grave in a garden of remembrance to the east of the churchyard, shaded with silver birch trees. On a flat stone is carved the winged sword emblem of the Auxiliary Air Force, in which he was a pilot. The headstone is a frame for a lovely figure of a woman with her hair in long plaits and a crown of stars on her head. Holding a sphere on which is a falcon, she represents Our Lady of the Sky, sculptured by Sir William Reid Dick. Seven shields on the back of the stone include those of his parents, Eton, Magdalen College, the City of Westminster, and Hertfordshire. A stone with five cherub heads round a star, marking the grave of Annie Louisa Sleath who was “forty years friend and Nannie of the Lutyens family, was designed by Sir Edwin.

The great Tudor house Sir Robert Lytton began to build was completed during the 16th century. Its original plan was of four sides enclosing a courtyard, and so it stood till the 19th century, when three generations of the family made it the house we see. The great transformation began in 1811 with the pulling down of three wings; then came the lavish enrichment of the remaining west wing with battlements, panelled turrets crowned with copper domes, stringcourses dotted with flowers and grotesques, dragons on pinnacles, and faces and gargoyles peeping out everywhere. The south wing with its tower-gateway was added last century. The wall round the other sides of the court is adorned with quatrefoils, and dragons holding shields are on the gateposts. The grounds are delightful with spacious lawns, formal avenues of pollarded limes, and carpets of primroses, daffodils, and narcissi under trees. A great almond tree is an entrancing sight in spring. There are noble avenues in the park, and near the church is a stone mausoleum decorated with urns and crowned with a sarcophagus.

The three rooms in the house which all may see belong mostly to the old mansion. As we enter we come upon a fine bronze bust of the earl of our time, Viceroy of India. In the staircase hall is a saddle and halter embroidered in solid silver, the gift of the Emir of Afghanistan to the first earl when he, too, was Viceroy. Here is a big array of armour of Queen Elizabeth I’s day, and some from the time of Cromwell; the Dutch musical clock is about 1700. Bulwer-Lytton converted the next room into the library, and here we see the novelist’s writing-table with his ink-stand, cigar-case, and blotting-pad. First editions of his works are on the shelves, and in a case are manuscripts of The Last Days of Pompeii, The Caxtons, and My Novel, a cast of the author’s hand, and letters he received from Charles Dickens. In the same case is the manuscript of Lucile, a novel in verse written by his son, the first earl, under the name of Owen Meredith. Treasured in another case are snuff-boxes which belonged to Charles Fox and William Pitt, Lord Byron’s ruler, a crucifix of gold and pearls which belonged to Mary Queen of Scots, the ink-stand used for the signing of the treaty between Charles I and the Commissioners of the Long Parliament, and a ring with a miniature of the king. It was one of three which Charles gave to his friends on the scaffold. Furnishing the library are chairs of the time of William and Mary and Queen Anne, and a 17th-century Spanish cabinet made of tortoiseshell, ebony, ivory, and gilt metal; and there is a long wooden pipe shown in a portrait of the novelist over the mantelpiece.

By a door disguised among the shelves of books we come to the charming white drawing-room, where nothing was lovelier when we called than the window peep of the laburnum trees flowering in a corner like a shower of gold. Here we see Sir Robert, the first Lytton of Knebworth, and among other family portraits are Peter Lely’s Ruth Barrington and Sir William Robinson Norreys. Hepplewhite and Chippendale are represented among the furniture; there are two tortoiseshell and ivory English cabinets of the time of Charles II, and another Spanish one of the same century. By Daniel Maclise’s portrait of Bulwer-Lytton as a young man is a door leading to the banqueting hall, a splendid chamber with an oak ceiling, screen, and gallery from the time of James I, and rich panelling said to have been designed by Inigo Jones. Most of the furniture here is Jacobean, but includes a valuable set of 12 applewood chairs, made in the time of Charles II. Portraits include one of the Duke of Gloucester, son of Charles and Henrietta Maria. Hanging here is a banner with the Lytton arms which hung above the throne from which Lord Lytton proclaimed Queen Victoria Empress of India at the great Durbar of 1877. One of the bedrooms has a noble four-poster richly carved in oak, in which Elizabeth I is said to have slept.

The first Lord Lytton was one of the most versatile men of all time in England. He was a novelist, dramatist, and politician, and succeeded in every ambition, though not to the extent of high and lasting eminence.

He was born in London in 1803, and brought up by his mother, his father dying when the son was four years old. From childhood he wrote poetry, and was expected to become a notable man. At Cambridge he took the Chancellor’s medal for a poem on Sculpture. He found popularity in prose when he was 25 with his novel Pelham, and he needed it, for he had only inherited £200 a year from his father, and his mother, who was well-to-do, had cut him off for marrying against her wishes. That marriage was a complete failure, except that from it have followed two generations of Lyttons honourably distinguished by public service. Lytton and his clever but hysterical wife could not live together, and they separated.

He soon had an ample income from his writings. Eventually the standard edition of his novels was issued in 48 volumes. The most striking feature of this enormous production, which was spread over nearly 50 years, was its variety in character and in style. His first series of stories, beginning when Scott was nearing the end of his wonderful career and before Dickens began his, owed something to the craze of Byronism, but soon became deflected into a study of crime, not unlike the crook element in fiction a century later. It began incidentally in Pelham, and continued in Disowned, Paul Clifford, and Eugene Aram, with Paul Clifford the highwayrnan as its most typical and popular example. Then he turned to history, with an attempt to build up round a central character a picture of a succession of ages past. The Last Days qf Pompeii, Rienzi, The Last of the Barons, and Harold illustrate this phase of his progress, for progress it was. He tried drama, not unsuccessfully in The Lady qf Lyons, Richelieu, and Money, plays that have attracted the public, in later years. In poetry he essayed the satirical and the romantic, but he failed in both. He made a vicious attack on Tennyson, who was then emerging into fame, and Tennyson retorted, in a poem that is not reproduced in his collected works, and (as Andrew Lang has said) knocked Lytton out in the first round.

Lytton now turned to the staple theme of fiction, the ordinary life of the people, and wrote his best novel The Caxtons, which was followed in the same quiet spirit but not with equal success by My Navel and What Will He Do With It? Later he sought to picture society and art as he saw them towards the end of his life in France and England, in contrast with what he had known in more aristocratic days. From time to time all through his life there was a strain of the eerie and abnormal in him, and in one of his last books, The Coming Race, he experimented in imaginative prophecy. He saw mankind’s powers of catastrophic destruction ensuring peace. Such an extraordinary range of interest in so many books could hardly be sustained, and Lytton, especially in his early periods, was often extravagant and melodramatic. He was adept in following popular fashions, and so failed in creating a style of his own. Though unquestionably clever, he never crossed the boundary line of greatness.

He sat in Parliament as a Whig for ten years and was offered a lordship of the Admiralty, but declined it. In 1852 he returned to Parliament as a Conservative, and was decidedly successful as a speaker. He served as Secretary for the Colonies, and was made a peer as Baron Lytton. Thrice he was elected Rector of Glasgow University. He died at Torquay in his 70th year.