Having been to Hatfield House with my youngest a couple of years ago, but without a camera (I wasn't collecting Hertfordshire churches then),I've visited St Etheldreda before and, as I remember, it is a magnificent interior with a much restored exterior. So I was disappointed to find it LNK but a subsequent Google search shows that it is normally open from 1-4pm when the house is open - a revisit is on the cards.

I revisited last week (22/05/14) and find that my memory of the interior was exaggerated: to call it magnificent is wildly inaccurate. In reality this is, typically of many Herts churches, as air brushed as the exterior; that is to say heavily refurbished in 1872 to the point of torpor. I think I was remembering the Salisbury chapel, which is really rather good, and the Burne Jones SE transept window (photos of which were unusable due to low light rendering them useless). To be honest I struggle to understand why Simon Jenkins rates this as a 3* church - I think I'd rate it 1* at best.

ST ETHELDREDA. The parish church and its churchyard lie on the top of an eminence. Down the hill run the main streets. Behind the church to the E is the entrance to Hatfield Palace and one of the entrances to Hatfield House. The W tower makes an impressive show from the high road below. It is of four stages, with set-back buttresses, a broad W door with quatrefoil decoration in the spandrels, and a four-light W window. The exterior of the nave is a disappointment after this first impression. It looks strikingly Victorian and was indeed rebuilt by David Brandon in 1872. He changed the windows from Perp to Dec, raised the roof, removed box pews and three-decker pulpit, and (strangest alteration of all) narrowed the chancel arch. In spite of all this the general impression of the interior is interesting, with its broad nave and the vistas through into the various openings of the E parts. These are in a more genuine condition and architecturally very remarkable. The church possesses a transept with the unusual adjuncts of two W chapels, and a chancel with a C15 S and a C17 N chapel. The chancel, transepts, and W transept chapels are the oldest surviving portions. They date from the C13, as can be seen from the inner jambs of the chancel E window with nook-shafts, the chancel Piscina, the blocked E lancet window in the S transept, and the blocked trefoil-headed larger opening to its N, and the surprisingly splendid arch between S transept and W chapel. This has trefoil responds with big dogtooth decoration between the shafts, large stiff-leaf capitals, and a complex arch section. The C15 added the W tower and the S chapel. Its arcade towards the chancel is unusually ornate. Instead of the customary four-shaft-four-hollow section the pier has four triple-shafts and above the hollows of the diagonals demi-figures of angels holding shields. The arch from the S chapel to the transept (which cuts into the C13 trefoil opening) is triple-chamfered and has no capitals between jambs and voussoirs. It looks as if it belonged to the C14, in which case a S chapel prior to the one now existing must be presumed.

Finally in 1618 William, Second Earl of Salisbury, built the N chapel as a mortuary chapel to hold his father’s tomb. The SALISBURY CHAPEL is the only part of the church which is stone-faced. Its windows are still entirely in the Perp tradition, but the three-bay arcade to the chancel has tall Tuscan columns (cf. Watford, 1595). Two bays are original, the third was added in the C19. The columns are of Shap granite, a material which was only coming into favour at the end of the Tudor era. The interior of the Salisbury Chapel was lavishly adorned by the third Marquis in 1871. The artists employed were Italians (cf. Hatfield House). There is plenty of Salviati mosaic and of alabaster used (the latter notably for the blind arcading of the N and E walls). The W and S openings are filled by exquisite iron gates of early C18 Flemish work which were brought by the third Marquis from Amiens Cathedral. In the chapel stands the MONUMENT TO ROBERT CECIL, First Earl of Salisbury, d. 1612. It was ordered by the second Earl from Simon Basyll, and the sculptures on it are by Maximilian Colt. The monument is entirely in the Dutch tradition, established by Tommaso Vincidor in the Nassau Monument at Breda. The Earl lies on a black marble slab supported by four kneeling allegorical figures: Faith, Justice, Fortitude, and Prudence. One of these has her breasts bare, a reminder of the distance which European civilization had travelled between the time when the church and when the chapel was built. But behind the four Virtues, below the effigy of the Earl in his full State dress, lies a skeleton on a rough straw mat, and that rude reminder of the vanity of worldly glory takes one back to the late Middle Ages. - In the same chapel are, moreover, the following MONUMENTS: A knight in armour, his chest covered by his shield, C13. - A body in a shroud on the floor; he lies relaxed, the attitude and the mastery of handling might be Italian. It is the effigy of Sir Richard Curle, by Nicholas Stone, 1617. Stone wrote in his notebook: ‘I mad a pector lieng on a grave ston of gre marbell for Mr Corell of Hatfield for which I had £20.’ - The Third Marquis of Salisbury d. 1903, Prime Minister to Queen Victoria, bronze by Sir William Goscombe John, replica of the monument in Westminster Abbey.

OTHER FURNISHINGS. PULPIT. By A. E. Richardson, 1947. Polygonal, with plain wooden panels with coloured shields. - ORGAN GALLERY. By W. H. R. Blacking, 1927. On Tuscan columns, arranged so as to let the light from the W window come in unimpeded. - COMMUNION RAILS. C17 with broadly twisted balusters. - CHANDELIER. Brass, given in 1733 (S chapel). - STAINED GLASS. Nothing medieval, but a good cross-section though Late Victorian glass. Infinitely the best the S transept window by Morris & Co., designed by Burne-Jones, 1894. It has a purity of glow, with its typical prevalent green and its peacock blue and rose-colour, never achieved by any other glass before the early C20. - Chancel E window and N chapel E window by Clayton & Bell, c. 1870-2. - The N windows of the N chapel and the E window of the S chapel by Burlison & Grylls, the former 1881, 1894, 1899, the latter, to the design of Temple Moore, 1902. - PLATE. Two Chalices and Patens, two Flagons, two Almsdishes, and a Spoon, all dated 1684 and all made for the Coronation of James II. - Cross and Candlesticks in the s chapel, designed by Temple Moore. - Processional Cross in the same chapel designed by A. E. Richardson. - MONUMENTS (other than those in Salisbury Chapel). Brass to Fulke Onslowe d. 1602, inscription on stone tablet (chancel, N wall). - Sir John Brocket d. 1598, very simple standing wall monument, without figures. Sir John was a merchant; yet his helmet is suspended above the tomb. - Dame Elizabeth Brocket d. 1612 and his mother. Big standing wall monument with the two ladies stiffly reclining, propped up on their elbows, one behind and above the other. The background architecture flat and not too costly. - Sir James Reade and his son John, by Rysbrack, 1760. Two busts, and above a portrait medallion against the usual obelisk. By the sides two big beautifully carved adult cherubs with large wings. - Thomas Fuller d. 1712, standing wall monument with inscription on drapery and two putti l. and r. ; not of high quality. - Several late C18 to early C19 epitaphs high up in the nave, particularly fine the Heaviside Monument by Thomas Banks, 1787, the side pieces later. In the centre two female allegories of Death (a reversed torch) and the Caduceus, the symbol of Medicine.

CHURCHYARD GATES. Magnificent ironwork taken to Hatfield from St Paul’s Cathedral. They were made about 1710.

Hatfield. It gathers itself about one of the greatest houses in the land, the home of the Cecils, built by the son of Queen Elizabeth I’s Burghley. He himself had built the great house of Theobalds, which James I took from Robert Cecil, giving him Hatfield in exchange. Sir Robert began the building of this marvellous place but never lived in it, for it was barely finished when his life was over and they laid him to rest in Hatfield church.

Here is a quiet little street where the old houses seem to mount in steps. It brings us to a delightful group of old buildings, clustering about and within the park. Picturesque cottages and a Georgian house look across to the church in its delightful setting of lawn and trees, carpeted in spring with crocuses and daffodils. At one corner of it is a timbered house, at another are iron gates which have a history, for they stood round St Paul’s, the iron having been foundried in Sussex in the days when iron founders were burning down forests instead of digging up coal. These gates were part of half a mile of iron railings ordered by Wren for St Paul’s, 200 tons of them. They stood in the heart of London till last century, when they were taken down to be sent to Canada. Only a few arrived, for the ship was wrecked and most of the railings now lie in the bed of the Atlantic.

Ending the vista of these buildings along the road is the brick gatehouse of the palace once occupied by the Bishops of Ely; what is left of the palace itself is across a lawn, a fine long range of mellowed brick with gables and a central tower, all 15th century. But a few steps away rises the great Hatfield House, nearly 100 yards long, with two wings projecting to the south, enclosing three sides of the great courtyard.

In Saxon days the land hereabouts belonged to the monks of Ely. Here in a few more generations grew up the home of the bishops of Ely, and in the 15th century Cardinal Morton began the building of Hatfield Palace. Brick had then become a popular material for builders, and in this great group of buildings no stone was used. What remains of the palace today is delightful. The gatehouse has ancient beams over its archway and a fine mullioned window above it, and the heavily buttressed west front of the palace itself is impressive, with a square tower, and a charming stepped gable at the end, crowned by a twisted chimney. The great hall remains with magnificent timbers in its roof, the solar and the room below it are intact, and there are splendid walls of open brickwork round the formal gardens. All this is now only the western range of buildings which once surrounded a square courtyard, and we see it as it has been much refashioned in Stuart times, and again last century.

In this great place all three of Henry VIII’s children spent much of their early years. Edward VI granted it to Elizabeth I and she was here when he died, her sister Mary being 12 miles away at Hunsdon. Here Elizabeth received an invitation to go to court to acknowledge Lady Jane Grey as queen. She refused, saying she was ill, but a few days more and she was well enough to go to town to proclaim her sister Mary, riding side by side with her into the City. Here Elizabeth was when Mary died on a grey November morning in 1558, a brilliant cavalcade riding down to Hatfield to bring the news; it is said that she received it under an oak still growing here.

A seat here has a carving of Elizabeth with her courtiers.

It was soon after the death of Elizabeth that Robert Cecil came looking round the grounds of the old palace for a site to build a house in place of Theobalds, which King James had coveted so greatly as to insist on changing it for Hatfield. Robert Cecil built the great house but never lived in it, dying before it was ready. It is built like an E in honour of Elizabeth, involving four years of hard work and costing about £40,000 in the money of that day.

It is one of the most magnificent houses in the land, with towers and domes and a marvellous array of windows. Only pictures can give any adequate conception of its splendour. The south porch rises to a great height with fluted columns one above the other and stone lions at the top, the date 1611, and winged cherubs who appear to be dancing round a coronet. Behind this rises the great clock tower with an octagonal cupola over it. The clock tower rises in three styles from the roof of the great hall and has an arch in the lower stage through which a motor-car could drive. There are sculptured figures at the corner of the upper stage, which are repeated at the top round the cupola.

The great hall is every inch superb, the east and west walls most richly screened and panelled, the north and south walls tapestried, and the ceiling arranged in compartments each with a painting set in a sculptured frame. The gallery on the east wall is divided into 12 panels, the top half of it open and the lower half like beautiful fretwork. Everywhere the doorways are stately, and the main staircase has probably never been surpassed. Its newel posts are works of art, carved with formal work and figures in relief and crowned with angry lions, fantastic creatures, and beautiful children with musical instruments. Like the hall, the chapel is two storeys high, with galleries on the upper storey from which we have a close view of the grotesque brackets set in the coved and painted ceiling; they are 16th century and were brought from the old Market House at Hoddesdon. The sanctuary is in the bay of a window crowded with Bible scenes, the work of French, Flemish, and English craftsmen in the 17th century. The front of the galleries is arcaded, and panelling covers the walls of the chapel below, which is entered through a handsome modern screen.

Two beautiful galleries run from end to end of the main building, the lower one known as the Cloisters or Armoury (from the suits of armour which stand as if guarding four splendid pieces of 400-year-old tapestry), and the upper one known as the Long Gallery which, with its anterooms, is 150 feet long. The ceiling of this gallery is superb, and the panelling which extends from it to the floor is a magnificent example of the reign of James I, especially the upper arcades, decorated with arabesques. Two of the great chimney-pieces which are so striking a feature of Hatfield House are here. In the niche of another marble chimneypiece King James presides in great pomp over the room named after him, the ceiling of which is ingeniously decorated with compartments of various shapes, elaborate pendants hanging down.

It need not be said that the house is filled with great possessions. There is the Rainbow portrait of Queen Elizabeth I by Zucchero, the death-warrant of Mary Queen of Scots, a letter in her handwriting, Lord Burghley’s diary recording the defeat of the Armada, one of Queen Elizabeth I’s hats and a pair of her stockings, a letter in the queen’s handwriting, a manuscript poem by Ben Jonson, a set of Benvenuto Cellini crystals given by Philip of Spain to encourage his suit with Queen Elizabeth I, a missal used by Henry VI (with his signature), and an Elizabethan quilt with mottoes and Tudor roses. As for the cradle in which Anne Boleyn is supposed to have rocked the little Elizabeth, it is believed that it is too late for that to have happened.

The wonderful park in which this famous group of buildings stands has the River Lea flowing at its northern end, covers 1300 acres, and is seven miles round. The entrance to its grand drive is off the Great North Road, and has four stone pillars crowned by lions holding shields, with beautiful gates and screenwork in which are satyrs, cherubs, and horns of plenty. In front of the gates, looking thoughtfully at the traffic passing by, sits one of the famous men of the last generation, the Conservative leader when Mr Gladstone was leading the Liberals to their triumph. He is the third Marquess of Salisbury, Prime Minister of England longer than any other man who has held the office.

His marble monument is in Westminster Abbey, near the grave of the Unknown Warrior, but he wished to lie here in the little burial ground by the church, and a simple tomb with a cross marks his grave. Inside the church is Sir William GoscombeJohn’s fine bronze of the marquess, showing him lying on a tomb of black marble, wearing a rich mantle with his Order of the Garter, and holding a Crucifix to his breast. Here also is the figure of the first Earl of Salisbury, who built the great house, sculptured in white marble by Simon Basyll. He is in his robes with a ruff, wearing the Garter and holding his staff, his head resting on embroidered cushions. The black marble slab on which he lies is borne on the shoulders of four white women representing the Virtues, two sitting and two kneeling on a black marble base. Below, under the marble shelf on which the earl lies, is a marble skeleton after the fashion of those days, a reminder that rank and power pass away and all are equal in the tomb. On the floor of the chapel are two memorials in stone, one the 12th-century figure of a knight with a great shield, the other believed to be William Curle, Warden of the royal estate at Hatfield. This Salisbury chapel, built by the first earl’s spendthrift son in 1618, is arresting with its classical arcade dividing it from the chancel, and lovely screens of delicate 18th-century ironwork looking like lacework. The 19th-century decoration is the work of Italian craftsmen. The walls have marble wainscoting, and both walls and ceiling are painted with the Four Evangelists, the parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins, and representations of the Virtues. Here lies a second Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, with his wife Lady Caroline Lamb; their grave is under the modern pulpit. One of the chapel windows is in memory of the mother of another Prime Minister, Lord Balfour.

In the south chapel are monuments of the Brockets and the Reades. The chapel was built at the close of the 13th century, and enlarged in the 15th when the arcade was set up dividing it from the chancel; it has capitals of angels holding shields. In its west wall is a 13th-century arch to the transept and a 15th-century doorway, and it has modern paintings of roses on its old roof beams. Here is the canopied tomb of Sir John Brocket, a merchant at the time of the Armada; he was a soldier, too, and his helmet hangs above his monument. Near him are two ladies lying stiffly one above the other, both with lifelike complexions, both wearing black dresses with white ruffs and cuffs, and one holding her gloves and resting her hand on a skull. One of the two is Sir John’s second wife, and the other is her mother, Dame Agnes Sanders. On an 18th-century monument are busts of Sir James and Sir John Reades, father and son, with a medallion portrait of Sir James’s daughter. They lived at Brocket Hall, which at their death passed to the Lambs and became the home of Lord Melbourne. It is a fine red house in a park three miles away, bounded by the Great North Road.

The church, one of the biggest in the county, is striking in its plan, the eastern half with chapels and transepts contrasting with the aisleless nave, which is spanned by a great modern roof with dormers doing duty as clerestory windows. It was built in the 13th century on an older site, but in the restoration of 1871 the nave was rebuilt, the rest of the walls were given new stonework, and the window tracery was renewed. New porches were built with timber from the old roofs, and the transepts, like the south chapel, keep most of their old beams. The massive tower and the arch leading from it to the nave are 500 years old. The south transept has the oldest work to show; coming from early in the 13th century are a. blocked lancet and a recess in its east wall, and a beautiful round-headed arch leading to its small west chapel, the mouldings deeply cut and the capitals carved with leaves. The chancel has a modern arch, and a reredos of alabaster and gold mosaic with a white marble Crucifixion scene, showing the three women and St John, and a saint on each side. There are Jacobean altar rails, an ironbound chest of 1692, an old pillar almsbox, a modern font with a 13th-century base, and a silver processional cross with the Twelve Disciples round the base. The lovely silver candlesticks and cross in the south chapel were fashioned from plate given to General Lindsay by five other Generals for his service in the House of Commons, and are now a memorial to his wife and daughter. The altar cloth of red plush embroidered with gold, was part of the pall at George III’s funeral. A treasure of the church is a piece of beautiful embroidery of roses and fruit in delicate colour and gold, of remarkable interest because it is said to have been worked by Queen Elizabeth I when she was at the palace. The handsome chandelier in the south chapel was given in 1733, the organ gallery is of 1927, and the pulpit of 1947.

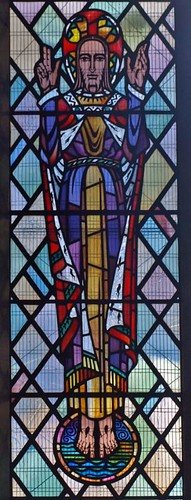

There are shields of old glass. A window designed by Burne-Jones has saints and small scenes illustrating the Virtues, in heavy colouring.

Hatfield has one of the three New Towns of Hertfordshire and what was a few years ago open farmland is now covered with thousands of mediocre houses and other buildings.