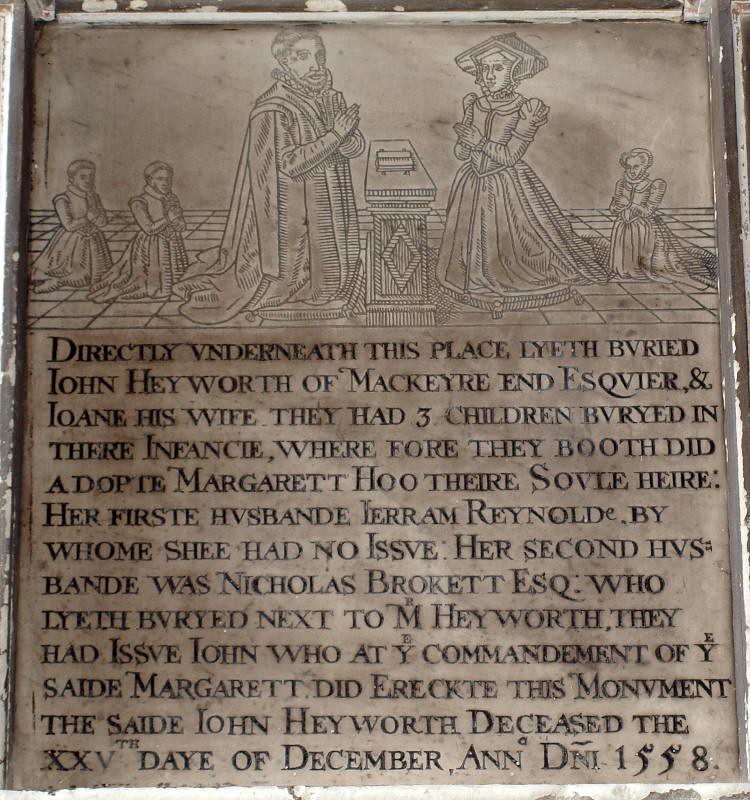

ST HELEN. A big flint church with a chancel as long as the nave and a dominating crossing tower with a broached lead spire starting like a pyramidal roof (an odd outline due to the C19 restoration). Of a Norman church the foundations of an apse have been discovered. The nave no doubt corresponded to the present nave. The chancel was added c. 1230 (see the fine group of three lancet windows in the E wall, with nook shafts inside, and the N doorway with dog-tooth decoration). The crossing tower with its heavy treble-stepped piers belongs probably to the later C13. The early C14 is responsible for the W door (with its ball flower ornament) and the S aisle and S porch. The two-light windows at the aisle W end and the octagonal piers with their moulded capitals and double-hollow-chamfered arches are typical of that date. Of the same date are the transepts, and here much money must have been available and an architect with a good sense of display. The N transept N window is of five lights, the S transept S window of four. Both have ogee-reticulated tracery. Moreover, the S transept E window has some very original finely ogee-cusped tracery and big fleurons inside along jambs and voussoirs. In the N transept the windows have even two orders of (smaller) fleurons. The E window has fleurons outside as well, and inside below the sill a delightful blank frieze of crocketed ogee arches with brackets for statuettes. Nothing else of the Dec style in the county, with the exception of the E end at St Albans, is quite so rich. The same designer inserted equally original windows in the chancel N and S walls. The N arcade of the nave is later than that of the S, although the N aisle has windows of early C14 date. The clerestory windows were given their present shape in 1863-6. The only notable contribution of the later Middle Ages is the charming canopied Piscina in the chancel tucked in diagonally by the Sedilia. - FONT. Early C14, octagonal with quatrefoil circles on finely carved but somewhat decayed leaves. - PULPIT. Jacobean, from the former chapel at Lamer House. - BENCHES. In the N transept. From the same chapel; two benches dated 1631. - SCREEN. Fragments in the N transept and at the W end, Jacobean, and probably made up of fragments from a former W gallery. - PAINTING. Mount of Olives by King, 1821, large figure. The frame is in a thin Gothic taste. - STAINED GLASS. Kempe, 1893, N aisle, first window from E. - MONUMENTS. A large number. Brass to Hugh Bostok and wife, c. 1436 (N transept); good large frontal figures; the parents of Abbot Wheathampstead of St Albans. - Brass to John Heyworth d. 1520 and wife (N transept), small figures slightly in profile. - Man and wife with children, c. 1520 (N transept). - Headless Lady, leg of a Knight and dog at his foot, C15 (S transept). * - Brass Indents chancel N with stone surround. - John Heyworth d. 1558 and wife (N transept), the figures small, incised in a marble slab, with a modest architectural surround; at the foot simplest strapwork (cf. Harpenden, Cressye). - Sir John Brocket d. 1558 and wife (S transept): alabaster tomb-chest with recumbent effigies. The decoration with figures and heraldry is just on the point of leaving the Gothic style and going classical. No refinements. - Garrard Monument N transept, the largest in the church, undated and not fully identified. The date must be in the 1630s, and the design is conservative for that date. Alabaster semi-reclining figures, the husband behind and slightly above the wife, big architectural surround and columns, coffered arch, and allegorical figures in the spandrels of the arch top achievement. - Many Garrard tablets in the N transept, one of them, hung up much too high to be seen, is by Thorwaldsen (Charles Drake G. d. 1817: two Grecian figures holding each other by the hand; in the style of Athenian stelae).

* The south transept is carpeted and I missed the north transept brasses.

Wheathampstead. As we walk about these lanes we may imagine a queer little man clinging close to his Bridget, drinking in the beauty of the countryside, and chatting eagerly in his delight at being here. He was Charles Lamb. Here are 400-year-old cottages he knew, a pleasant inn of the same old age, and a church with stone and brass memorials of no less than 50 folk of medieval days. But the hills looking down on them all, the River Lea cutting its way through, and the wild Heath of No Man’s Land carry memories far more ancient than these.

The heath took its name, it is said, from its position as the dividing land between the domains of the abbots of St Albans and the abbots of Westminster. Round about are entrenchments dug before the days of history. A boundary dyke, in places 32 feet deep and 100 feet across the top, runs for a mile from Bernard’s Heath to St Albans Road. To the south-east Devil’s Dyke and the Slad, both now protected by the National Trust, run nearly parallel. Were these the fortifications where the British tribe turned Caesar’s raiding forces back?

History speaks with more assurance at Mackery End, the 16th-century farmhouse delightful with its elegant gables and famous for its place in literature, for here Charles Lamb as a weakly child lived with the Gladmans in the tender charge of his Bridget. His memories of those days, recalled by a visit 40 years later, make one of his most delightful essays:

The oldest thing I remember is Mackery End, a farmhouse delightfully situated within a gentle walk from Wheathampstead. I can just remember having been there, on a visit to a great-aunt, when I was a child, under the care of Bridget, who, as I have said, is older than myself by some ten years. . . .More than forty years had elapsed since the visit I speak of; and who or what sort of persons inherited Mackery End (kindred or strange folk) we were afraid almost to conjecture, but determined someday to explore.

By somewhat a circuitous route, taking the noble park at Luton in our way from Saint Albans, we arrived at the spot of our anxious curiosity about noon. The sight of the old farmhouse, though every trace of it was effaced from my recollection, affected me with a pleasure which I had not experienced for many a year. For though I had forgotten it, we had never forgotten being there together, and we had been talking about Mackery End all our lives.

Bridget’s was more a waking bliss than mine, for she easily remembered her old acquaintance again, some altered features, of course, a little grudged at. At first, indeed, she was ready to disbelieve for joy; but the scene soon reconfirmed itself in her affections, and she traversed every outpost of the old mansion, to the woodhouse, the orchard, the place where the pigeon-house had stood (house and birds were alike flown) with a breathless impatience of recognition, which was more pardonable perhaps than decorous at the age fifty- odd. But Bridget in some things is behind her years.

The only thing left was to get into the house, and that was a difficulty which to me singly would have been insurmountable; for I am terribly shy in making myself known to strangers and out-of-date kinsfolk. Love stronger than scruple winged my cousin in without me; but she soon returned with a creature that might have sat to a sculptor for the image of Welcome. It was the youngest of the Gladmans; who, by marriage with a Bruton, had become mistress of the old mansion. A comely brood are the Brutons. Six of them, females, were noted as the handsomest young women in the county. But this adopted Bruton, in my mind, was better than they all - more comely.

Those slender ties that prove slight as gossamer in the rending atmosphere of a metropolis bind faster, as we found it, in hearty, homely, loving Hertfordshire. In five minutes we were as thoroughly acquainted as if we had been born and bred up together. . . . The fatted calf was made ready, or rather was already so, as in anticipation of our coming; and, after an appropriate glass of native wine, never let me forget with what honest pride this hospitable cousin made us proceed to Wheathampstead, to introduce us (as some newfound rarity) to her mother and sister Gladmans. . . . When I forget all this, then may my country cousins forget me; and Bridget no more remember that in the days of weakling infancy I was her tender charge, as I have been her care in foolish manhood since, in those pretty pastoral walks, long ago, about Mackery End in Hertfordshire.

In an older Mackery End than this was born John of Wheathampstead, the famous abbot of St Albans who founded the abbey library and whose tomb still graces the abbey church. He was a powerful man in the 15th century. In the church at Wheathampstead his proud parents, Hugh and Margaret Bostock, are portrayed in brass. Other portraits in the north transept picture John Heyworth and his wife, a Tudor couple with their nine children, and another nameless couple of those days are here with eight children not their own, for they do not fit the stone. We may suppose they come from one of the stones in the chancel and the south transept, where are fragments of many other brasses.

The north transept was the chapel of the Garrard family of Lamer Park, where their shields still appear on a 17th-century entrance arch and in the window of the dairy, which was once a chapel. From that chapel at Lamer Park (older than the house, which is 18th century) came the church’s oak pulpit and two chairs, all 17th century. A whole family of Garrards appear in the transept on a coloured marble monument of 1637, Sir John (one of the earliest of our baronets) in armour with his wife, and below them in relief six sons and eight daughters. Opposite is a white stone cut with a sketch of John Heyworth of 1558 kneeling with his wife and three children, and on their tombs in the south transept lie the alabaster figures of Sir John Brocket in 16th-century armour with his wife. Round the tomb eight mourners stand out in relief. On the chancel walls we read of Nicholas Bristow, servant to the last four Tudor sovereigns, and of Thomas Stubbinger, who in the 17th century seems to have successfully combined the business of a merchant with the life of a rector.

The foundations of an earlier apse show that there was a church here in Norman or perhaps in Saxon days, but the oldest part of the present building is the chancel, with its stringcourse and three lancets of the 13th century. The central tower, with its odd spire and graceful arches, was rebuilt at the end of that century. The tracery of the 14th-century builders fills the windows of both transepts and both aisles; theirs are the arcades and the ballflower arch of the west doorway, the font, and the rare stone reredos of seven canopied niches in the north transept, where the sill of the east window is brought low to support this treasure, with all its delicate detail. The screen to this transept was made from the timbers of a gallery of 300 years ago.

The heath took its name, it is said, from its position as the dividing land between the domains of the abbots of St Albans and the abbots of Westminster. Round about are entrenchments dug before the days of history. A boundary dyke, in places 32 feet deep and 100 feet across the top, runs for a mile from Bernard’s Heath to St Albans Road. To the south-east Devil’s Dyke and the Slad, both now protected by the National Trust, run nearly parallel. Were these the fortifications where the British tribe turned Caesar’s raiding forces back?

History speaks with more assurance at Mackery End, the 16th-century farmhouse delightful with its elegant gables and famous for its place in literature, for here Charles Lamb as a weakly child lived with the Gladmans in the tender charge of his Bridget. His memories of those days, recalled by a visit 40 years later, make one of his most delightful essays:

The oldest thing I remember is Mackery End, a farmhouse delightfully situated within a gentle walk from Wheathampstead. I can just remember having been there, on a visit to a great-aunt, when I was a child, under the care of Bridget, who, as I have said, is older than myself by some ten years. . . .More than forty years had elapsed since the visit I speak of; and who or what sort of persons inherited Mackery End (kindred or strange folk) we were afraid almost to conjecture, but determined someday to explore.

By somewhat a circuitous route, taking the noble park at Luton in our way from Saint Albans, we arrived at the spot of our anxious curiosity about noon. The sight of the old farmhouse, though every trace of it was effaced from my recollection, affected me with a pleasure which I had not experienced for many a year. For though I had forgotten it, we had never forgotten being there together, and we had been talking about Mackery End all our lives.

Bridget’s was more a waking bliss than mine, for she easily remembered her old acquaintance again, some altered features, of course, a little grudged at. At first, indeed, she was ready to disbelieve for joy; but the scene soon reconfirmed itself in her affections, and she traversed every outpost of the old mansion, to the woodhouse, the orchard, the place where the pigeon-house had stood (house and birds were alike flown) with a breathless impatience of recognition, which was more pardonable perhaps than decorous at the age fifty- odd. But Bridget in some things is behind her years.

The only thing left was to get into the house, and that was a difficulty which to me singly would have been insurmountable; for I am terribly shy in making myself known to strangers and out-of-date kinsfolk. Love stronger than scruple winged my cousin in without me; but she soon returned with a creature that might have sat to a sculptor for the image of Welcome. It was the youngest of the Gladmans; who, by marriage with a Bruton, had become mistress of the old mansion. A comely brood are the Brutons. Six of them, females, were noted as the handsomest young women in the county. But this adopted Bruton, in my mind, was better than they all - more comely.

Those slender ties that prove slight as gossamer in the rending atmosphere of a metropolis bind faster, as we found it, in hearty, homely, loving Hertfordshire. In five minutes we were as thoroughly acquainted as if we had been born and bred up together. . . . The fatted calf was made ready, or rather was already so, as in anticipation of our coming; and, after an appropriate glass of native wine, never let me forget with what honest pride this hospitable cousin made us proceed to Wheathampstead, to introduce us (as some newfound rarity) to her mother and sister Gladmans. . . . When I forget all this, then may my country cousins forget me; and Bridget no more remember that in the days of weakling infancy I was her tender charge, as I have been her care in foolish manhood since, in those pretty pastoral walks, long ago, about Mackery End in Hertfordshire.

In an older Mackery End than this was born John of Wheathampstead, the famous abbot of St Albans who founded the abbey library and whose tomb still graces the abbey church. He was a powerful man in the 15th century. In the church at Wheathampstead his proud parents, Hugh and Margaret Bostock, are portrayed in brass. Other portraits in the north transept picture John Heyworth and his wife, a Tudor couple with their nine children, and another nameless couple of those days are here with eight children not their own, for they do not fit the stone. We may suppose they come from one of the stones in the chancel and the south transept, where are fragments of many other brasses.

The north transept was the chapel of the Garrard family of Lamer Park, where their shields still appear on a 17th-century entrance arch and in the window of the dairy, which was once a chapel. From that chapel at Lamer Park (older than the house, which is 18th century) came the church’s oak pulpit and two chairs, all 17th century. A whole family of Garrards appear in the transept on a coloured marble monument of 1637, Sir John (one of the earliest of our baronets) in armour with his wife, and below them in relief six sons and eight daughters. Opposite is a white stone cut with a sketch of John Heyworth of 1558 kneeling with his wife and three children, and on their tombs in the south transept lie the alabaster figures of Sir John Brocket in 16th-century armour with his wife. Round the tomb eight mourners stand out in relief. On the chancel walls we read of Nicholas Bristow, servant to the last four Tudor sovereigns, and of Thomas Stubbinger, who in the 17th century seems to have successfully combined the business of a merchant with the life of a rector.

The foundations of an earlier apse show that there was a church here in Norman or perhaps in Saxon days, but the oldest part of the present building is the chancel, with its stringcourse and three lancets of the 13th century. The central tower, with its odd spire and graceful arches, was rebuilt at the end of that century. The tracery of the 14th-century builders fills the windows of both transepts and both aisles; theirs are the arcades and the ballflower arch of the west doorway, the font, and the rare stone reredos of seven canopied niches in the north transept, where the sill of the east window is brought low to support this treasure, with all its delicate detail. The screen to this transept was made from the timbers of a gallery of 300 years ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment