I visited four churches, St Mark, Holy Saviour, St Faith and St Mary, but only one really counts and that is St Mary.

Holy Saviour, lnk, is an 1865 Butterfield build and rather bland, St Faith, lnk, is utterly devoid of interest and St Mark, which does have the merit of being open, is a drab 1936 build.

St Mary is a large wool church and is without doubt one of the top ten churches in the county but as both Pevsner and Mee have long entries I'll leave it to them to extol its virtues.

ST MARY. The church is different from all other Herts parish churches in that it is evidently a building representing the commercial wealth of a late medieval town. As in most English towns the source of the wealth was wool. The building has a nave and aisles of five windows and a chancel and chancel chapels of five windows, the chancel chapels projecting exactly as far as the chancel. Thus the E view, from where the town has opened it up to the nicely landscaped river, is of three parts with their large 5-light windows, the aisles low-pitched with battlements, the chancel flat-topped with angle pinnacles and battlements. The church is in fact embattled all round, one of the usual ways to express importance and money spent. The most spectacular piece is the S porch, two-storeyed with an E staircase turret, two bays, window openings on the W and E sides, an elaborate lierne-vault inside, an inner doorway of six orders of thin colonnettes, and an outer doorway with above it a three-light window and four niches with brackets for statues and a relief of the Trinity in the central battlement. The arms of the Staple of Calais prominently displayed on the S wall. This porch was probably paid for by Nicholas Mattock, a rich merchant of Hitchin. The N porch is also two-storeyed. The N and S windows of aisles and chancel chapels are all Perp, large, and of three lights. There are, however, other differences between nave and chancel. The nave is flint, the chancel chapels stone, the nave battlements are flint, those of the chancel renewed in brick. Much brick has also gone into repair work of the relatively low W tower (with spike) which, in spite of its angle buttresses, was begun in the C12 and completed in the C13. Under the angle buttresses early flat buttresses have been found. The W door is obviously E.E. (two orders of shafts with moulded capitals and voussoirs of complex section), the windows on the bell-stage are also E.E., the stair-turret starts rectangular, before it becomes polygonal, and the treble-chamfered tower arch towards the nave can well be of the C13 too.

The general impression of the church from outside is one of comfortable spaciousness, an impression which the interior bears out. Nave arcades of octagonal piers with double-chamfered arches, early C14, With a clerestory irregularly added in the C15, four-centred chancel arch erected at that time above the responds of an earlier one, and chancel of four bays with stone piers with shafts in the main axes and hollows in the diagonals. Irregularities at the E end of the chancel (where a charnel-house is built underneath) and at the junction of nave and chancel. Oddly enough the nave has four bays but the aisles four windows and the porches, that is five bays, and the chancel has also four bays and the chancel chapels five windows. No building dates are recorded.

Uncommonly fine series of ROOFS. The flat ceiling in the N aisle with its broadly and beautifully cusped panels looks early C14, the S aisle and S chapel, nave, and chancel roofs are all C15. That of the S chancel chapel has principals resting on stone angels and sub-principals with long wooden angel-figures at their feet.

Uncommonly fine series of SCREENS. N and S chancel chapel to N and S aisles and Parclose Screens to the chancel. The latter are, of course, simple, but the W screens are richer than any other in the county and differ from each other in design. No standardization of tracery design in the Parclose Screens either. - FONT. Stone, C15, with mutilated figures under ogee canopies. - PULPIT. With angle buttresses and restored C15 panels. - BENCHES. Some with poppy-heads in the chancel. - DOOR. Impressive S door with cusped panels, C15. - PAINTING. Adoration of the Magi, Flemish, C17. - PLATE. Patens, 1625 and 1634; Salver, 1635; two Chalices and two Flagons, 1705. - MONUMENTS. Many, but none of great importance. They will be given here topographically. Chancel: Brass to a priest, largish, late C15. - Brass to a man and woman in shrouds with children, late C15. - Brass to a man d. 1452, wife and children, large frontal figures. - Brass to a woman, late C15, the figure much rubbed off. - Brass to a man with three wives, late C15. - N Chancel Chapel: Three C15 tomb-chests with quatrefoil and heraldic decoration, on two of these brasses (John Pulter d. 1485; civilian and wife). - Brass to a shrouded young woman with hair let down. - N Aisle: On window sills three defaced stone effigies, one mid C13, the other two late C14. - Epitaph to Ralph Skinner d. 1697, with scrolly pediment, flowers and garlands, but no figures (by Stanton, according to Mrs Esdaile). - S Chancel Chapel: Many epitaphs, notably to four Radcliffes, c. 1660. - S Aisle: Brass to a shrouded woman with children. - Brass to a man with indent of wife. - Nave, W end: Mid C15 brass to a civilian and wife. - S. Aisle: Epitaph to Robert Hinde d. 1786, by Chadwick of Southwark, with a female standing under a palm tree.

HOLY SAVIOUR, Radcliffe Road, 1865, by Butterfield, and in every way a full-blooded example of his style: E.E. of red brick with stone and blue brick dressings; no tower; only a W bellcote, the W front with two windows and three buttresses so that one runs up the centre of the facade. Interior rather dark, as all windows have stained glass. Short rectangular piers without capitals, and walls decorated with sgraffito, white brick, red brick. and blue brick in complex diapers. Twice as many clerestory windows as arcade arches. Thin iron Screen with trefoil arched tops to the sections.

Hitchin. It is old-world England wherever we turn in this small town, with one of England’s smallest rivers flowing by Hertfordshire’s biggest parish church. It is the River Hiz, ten miles long. The streets are attractive with old houses, some so low that we may touch the eaves from the pavements, and there are three groups of attractive almshouses, 16 in the street called Bancroft, glowing in the sunshine behind pretty gardens; the Skynner almshouses of the 17th century; and, most delightful of all, the Biggin almshouses by the church and by the river, a mellow group of tiled and gabled roofs and leaded windows looking out on a courtyard enclosed by a cloister with wooden columns, and with medieval stones from a nunnery built into the walls. The Hermitage is an irregular building linked up with a 16th-century timbered barn. In its garden are traces of ancient cultivated terraces.

Church House was at one time a school, and one of its schoolmasters was Eugene Aram; it is said that the vicar, Pilkington Morgan, once preached before him on divine retribution. A house called Mount Pleasant, standing on the higher ground of the town, was the birthplace in 1559 of the famous George Chapman, and has on it a tablet reminding us of his claim to immortality. It was here during Shakespeare’s day that Chapman produced an enormous output of comedies, tragedies, and poems, though he is chiefly remembered now not for the plays with which he collaborated with Ben Jonson, but for the translation of Homer which so stirred Keats, as he tells us in that sonnet beginning:

Much have I travelled in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen.

This is the inscription on the tablet on Chapman’s birthplace:

The learned shepherd of fair Hitchin Hill, as his young contemporary William Browne describes him in his Britannia’s Pastorals, himself records in The Teares of Peace that it was while he was “on the Hill next Hitchin’s hand” the shade of Homer filled his bosom with a “floode of soule.”

The great medieval church, with a little Garden of Rest beside it is rich in craftsmanship of the 14th and 15th centuries. Its tower is older still, for it stands on Norman foundations and has Roman bricks in it. Its doorway is 13th century. Though Hitchin was a home of Nonconforrnity, it would seem that the congregation at this church was glad to have the Stuarts back, for the sundial on the wall of the tower has a Latin inscription reading, In the year of security 1660. The porch is magnificent, with many niches filled with statues 400 years ago. It has two storeys, with pinnacles crowning the walls, and a carving of the Holy Trinity over the doorway. The vaulted roof has carved bosses, and a room above it (now a small museum) has in it a 14th-century tile of a man with his right arm across his chest and his left arm pointed upwards, supposed to be the builder of the church. The door opening for us into the church has been swinging on its hinges 500 years. The font is of the same age, and has 12 sides on each of which is the figure of a saint under a beautiful canopy; its cover is like a lovely spire.

It is an impressive interior into which we come. Most of the roofs are 500 years old, with wooden angels looking down from them into the chapels, and among the stone corbels are portraits of Edward III and his Queen Philippa, a beggar feeding from a bowl, and an angel and a demon both whispering into the ears of a girl. The roof of the north aisle is partly older still, the elaborate cusping in its panels being the work of a 14th-century craftsman. The screens are striking and beautiful, particularly the 15th-century screen of the south chapel, which has a central bay with two bays on each side, all with lovely window tracery, a row of quatrefoiled arches and shields above them, and over this a cresting of angels. The work of the medieval craftsman is also in some of the bench-ends of the chancel and in the traceried panels of the pulpit. The unusual length of the chancel is one of the striking features of the church. Hanging on a wall is a painting of the Adoration of the Wise Men which is said to be by Rubens.

The church has a big collection of brasses, most of them worn and of unknown people. On the floor of the chancel are portraits of a 15th-century priest, James Hert, an unknown merchant of 1452 with his wife and ten children, and another unknown with his wife in shrouds and their eight children.

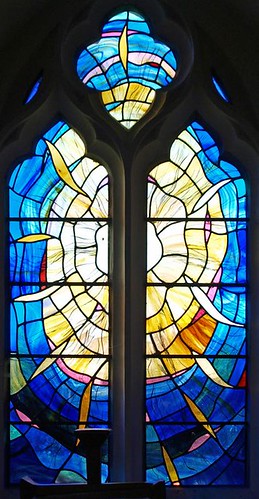

In the south aisle Margery Beel is engraved with her eight children and in the nave is a civilian with three wives and another unknown family of ten, all of the 16th century. Against the wall of the north chapel are three 15th-century tombs in a row, one having the brass portraits of a man and his wife, the second a man with his wife in shrouds, and a third with the name of John Poulter, a draper. An unknown 13th-century knight in the nave, much worn after 700 years, lies on the window-sill of the aisle leading to the north chapel, and there are two other marble figures here of a knight and his lady in 14th-century costume. The first of these figures is believed to represent Bernard Baliol, an ancestor of the man who founded Balliol College, and the knight with his wife is Edward de Kendale, who fought at Crécy and Poitiers and helped to quell the disorders in Hertfordshire which followed the Black Death. In the south chapel are the memorials to the Radcliffe family, who lived in Hitchin for 12 generations; the east window showing Christ stilling the waters is in memory of one of them. Two other windows are notable, one in memory of three brothers, John, Frank, and William Hawkins, benefactors of the town, the other the peace memorial window, showing St George in gold armour, Christ red-robed and crowned, and the Archangel Michael in silver grey. Below these fiigures are panels of St George slaying the dragon, Satan cast out of Heaven, and St Andrew.

An interesting man lies under the south aisle, Captain Robert Hind, the original of Laurence Sterne’s Uncle Toby in Tristram Shandy Who does not remember Uncle Toby and the corporal at the lieutenant’s deathbed, the corporal insisting that he must die, Uncle Toby insisting that he shall live?

“He shall not die, by God,” cried my Uncle Toby. The Accusing Spirit, which flew up to heaven's chancery with the oath, blushed as he gave it in; and the Recording Angel, as he wrote it down, dropped a tear upon the word and blotted it out for ever.

Hitchin has a modern church founded by the first vicar, George Gainsford, and built in 1865 by the well-known architect William Butterfield. It has much interest, having a small gallery of pictures by well-known artists. One is the head of the Madonna by Carlo Dolce, another is the Good Shepherd by Frederick Shields, a third is a good copy of Raphael’s Entombment, and a fourth is the Nativity probably by a Flemish artist. In the sanctuary are two gilded candlesticks which once belonged to John Mason Neale, the famous writer of hymns who founded a religious community at East Grinstead in Sussex.

Hitchin has an interesting possession in a chapel, for in the Baptist Chapel in Tilehurst Street is a chair John Bunyan gave to the minister in his day. Behind the chapel is a graveyard in which lies Agnes Story, who as a girl was Agnes Beaumont, a devoted follower of Bunyan. She figures in a story which must have been a source of much distress to Bunyan. Her father, a farmer at Edworth in Bedfordshire, had been much moved by the tinker’s teaching and her own name is entered in Bunyan’s handwriting in the register at Gamlingay, of which he was pastor. It happened, however, that the father lost his love for Bunyan, and Agnes, who had become an ardent disciple, found it difficult to obtain permission to attend the meeting-house. She had arranged on one occasion to go with a minister from her brother’s house to hear Bunyan, but as the minister did not turn up John Bunyan rode over to take his place. John Beaumont lifted his wife on to his own horse and Bunyan lifted Agnes Beaumont on to his. The father, looking out from the fields and seeing what had happened, was indignant, and barred the door against his daughter, so that she spent the night in a barn and afterwards took refuge at her brother’s house. The next Sunday she decided to obey her father and went home again, and in two days, by a dramatic stroke of fate, her father died suddenly. The story was spread abroad that he had been poisoned, and there was scandal and enquiry, but Agnes was acquitted, she having been entirely innocent.

To the South of Hitchin is a lovely park of over 100 acres in which stands all that is left of Hitchin Priory, now incorporated in the old home of the Radcliffes. Most of it was built in the 18th century, but there is a beautiful arcade and panelling from its 17th-century predecessor, with fragments also of the medieval house of the White Friars.

At Hitchin was born (brought up at the 17th-century gabled house called The Grange) the famous Sir Henry Hawkins, an unrivalled criminal judge for about 20 years of the last generation. His court was always crowded, though he sat long hours and kept every window shut. He died as Lord Brampton, and is chiefly remembered because he won his spurs in the romantic Tichborne case.

There was born at Charlton hereabouts, in 1813, a man with over a hundred inventions to his credit, the chief of them being the manufacture of steel. He was Sir Henry Bessemer. During the Crimean War it was felt that there was weakness in the metal used for guns, and Bessemer began fusing cast-iron with steel. During his researches he found that fragments of iron which had been exposed to an air-blast remained solid in spite of intense heat, and on touching them with an iron bar he discovered that they were merely shells of decarbonised iron. He instantly realised that by the aid of the air-blast iron could be entirely freed of carbon, the unknown quantity removed and the desired quantity introduced at will. The process created a great sensation, but early experiments failed and iron-masters who had clamoured for licences to use the process abandoned them in scorn. But Bessemer went on, brought his invention to triumphant success, and was soon selling steel £20 a ton cheaper than his rivals. He was on a flowing tide, and added new resources to engineering all over the world.

We know from George Chapman’s own pen that he was a Hitchin man, born in 1559. It is believed that he was at Oxford, where, according to tradition, although he excelled in Greek and Latin, his weakness in logic and philosophy prevented his gaining a degree.

He was closely associated with Ben Jonson, who “loved him,” with Spenser, Marlowe, and others of the immortals, and he attested his friendship for Inigo Jones by dedicating one of his plays to him. As poet and dramatist he filled a high place in Elizabethan England, but his original poems and his 18 dramas are dead beyond revival. In an age whose every breath seemed charged with inspiration, Chapman had his hours of serene inspiration, and left us examples of lofty thought, snatches of lyric passion, flashes of humour and satire (one exercise in which, supposed to reflect on the needy followers of James I, landed him in prison). Generally, however, he is arid, ponderous, and dull.

But as a translator he soared supreme, and his Homer earned him undying fame. It was here that he translated the last 12 books of the Odyssey in 15 weeks!

The work was begun for Prince Henry, from whom he had expectations of high preferment; and with the death of that bright hope for England Chapman wrought in a sustained ecstasy, as if the spirit of Homer himself animated his faculties. Marred by occasional obscurity, harshness, and mistakes in Greek, the work yet remains the finest metrical translation of Homer we have. It was superseded by Pope’s translation with its modern spelling and idiom, for every age requires its new translation of the Father of Poets, but it was Chapman that Keats found “Speak out loud and clear,” Chapman’s Homer which caused Keats to break faith with his own deathless sonnet:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken.

Thus at a stroke the names of Keats, Chapman, and Homer are linked in lines that will sing the Elizabethan’s glory as long as an Englishman survives to read his mother tongue.

Flickr.